The process of creating a new familiar

The process of creating a new familiar

what if a desktop was made like a laptop?

It was 2009 and PC's were changing - for good. The desktop model was really about one thing and one thing only: power for cheap. The industry relied on a standardized channel of components which were interchangeable and available in high volume across a wide spectrum of manufacturers. Everyone was making the same thing, selling the same thing, with only the hope of beating the competition on cost. This is how the mega-brands like Dell and Gateway came into prominence: they gave consumers direct access to the channel, allowing customers to build their own configurations out of stock parts, based on specs, and have them delivered...essentially in a box...with either a Gateway badge or a Dell badge on the front.

But things were changing. Big, boxy desktops were fading from popularity and another category (made popular by the iMac) was starting to emerge as the choice for home PCs: the All in One PC. These are PCs which are built into the monitor, allowing the consumer to buy the whole system in one go: monitor, keyboard, mouse and PC all wrapped up in one elegant package. Add to this the fact that Mobile was starting to catch up in specs to the desktop offerings. What was remarkable to me, was that the mainstream had yet to marry these two trends. All of the All in Ones on the market were still packaging those clunky channel components which were made to fit into beige boxes under the desk. The LG V300 began as an exploration of what might happen if you combined and All in One with the efficiency and elegance of a custom mobile architecture. The result of this experimentation, at the time, was a striking contrast to the status quo.

It Started With a Concept

It Started With a Concept

it started with a concept

The LG V300 began its life as an architecture concept named "Modo." Since we never knew what brand might end up carrying our designs, we liked to put placeholders for the brand name. The standard practice at Intel is to name product concepts after geographic locations (Hence NorthCape, Cove Point, and various other provincial concept names in my portfolio). When given the choice, I prefer using a short, piffy name for the placeholder. Something people will remember. In this case Modo would do.

Modo had a simple objective: How could we make an All in One an "invisible architecture"? By that I mean, how could we eliminate the concept of technology from the User experience, and instead present an object that was designed to be seen and interacted with from all sides? For me, this meant subverting the concept of a "back" of the all in one. No more attractive bezels and facades which only seek to conceal a horrid and confusing backside (populated by screws, vents and access panels). Instead I designed Modo to be crafty about concealing its need for thermal venting, for fastening during assembly, for customization and maintenance somewhere down the line. I even wanted the IO (input/output) to be concealed if it wasn't in use - borrowing a bit, perhaps, from the macbook air which had come into the market with intriguing bomb bay doors at the IO.

And Got Better From There

And Got Better From There

And got better from there

The Modo Concept was getting a lot of attention at this point - not just because the product felt compelling, but because there was a real business opportunity for Intel. If we could establish a benefit to introducing mobile architectures (which came with some nice margins) to what were traditionally desktop products, we could be looking at a pretty nice boost to the bottom line.

It was important to me, though, that this not be a simple discussion about making All In Ones "thinner and lighter." The real win - and the obvious difference that would tip the scales, would come from real diligence about achieving a clean product which was pure interaction. This meant we had to re-think the All in One entirely and drive to solutions that might convey the same utility and sophistication as what we were starting to expect from the mobile space.

One example or re-think came from the thermal design. For those of you who design PC clients, you know that thermal performance is the key to everything. If you want speed, you need power, if you have power you get heat. It is essential to remove heat from the system as quickly and efficiently as you can. One of the first reactions to Modo was "oh, you're going to have to poke a lot of vents in that." No one believed you could achieve a high-performance system without the cacophony of holes and vents you commonly find in AIO's. No one except the Thermal Engineer on my team: Konstantin Kouliachev. He was able to devise a way for the airflow to pressurize and travel through the system through one large (and therefore very quiet) fan and one outlet. The result was a design which was not only very effective, but also minimal in presence.

The process of creating a new familiar

The process of creating a new familiar

we wanted to PUT things where you could reach them

The next re-think was regarding access. In typical AIO's all of the connectors and components are housed together - hardwired to the motherboard. Unfortunately for the user, the motherboard inevitably sits behind the screen. That means if you want to plug something in or burn a CD or something, you have to stand up and reach behind the screen get the job done. It's tedious, and strictly a product of engineering efficiency taking priority over user experience. The original MODO concept accepted this as a constraint, but over time it became clear that we had to make this experience better. Once again, the solution was to take advantage of smaller, more efficient mobile components to move all of the important access stuff to the base. It wasn't easy, but Tim Nguyen figured out how to wire and cable a 9.6mm BluRay ODD and IO board in a way that worked wonderfully and still preserved a magically thin base.

Weeks in Taipei

Weeks in Taipei

MANY TRIPS TO TAIPEI

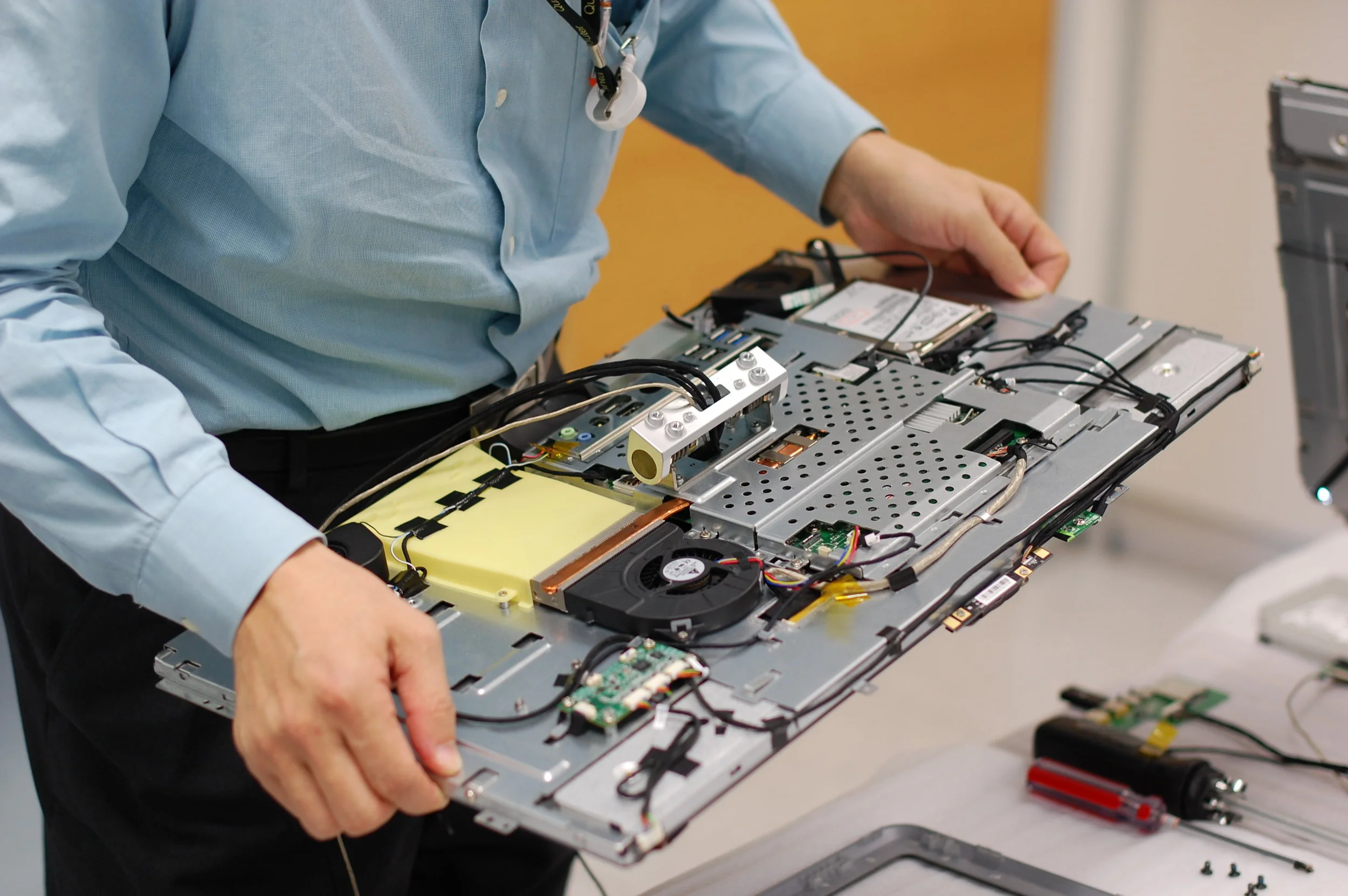

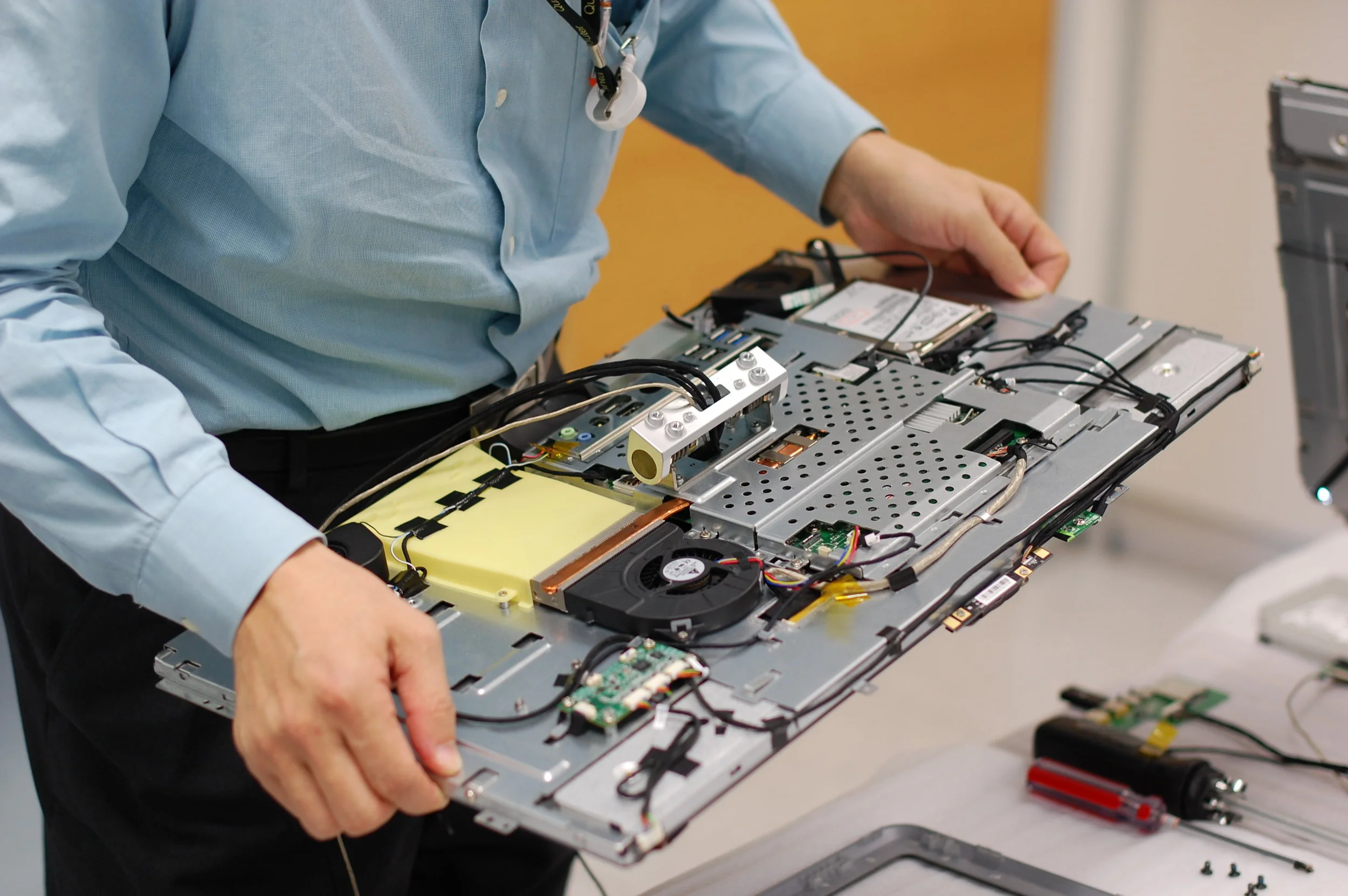

Having progressed from concept to a refined design, it was time to engage with a manufacturing partner. Quanta (a major ODM based out of Taipei) signed on for the project and we worked together to refine the design further, this time with manufacturing in mind. I remember when one of the Quanta project managers asked me how I would like to get the metal appearance of the back of the system...I said, "well I'd like to make it out of metal." At this point all 20 of the project engineers laughed at once.

After several months of conference calls and days sitting in Taipei conference rooms drawing on whiteboards, the DVT 0 (Design Validation Test Unit) was ready for assembly and power on. Here are some photos of that inaugural build:

Attention to Detail.

Attention to Detail.

attention to detail becomes a daily battle

We were thrilled when LG signed on to bring our All in One into their product line. This would be their flagship product in the desktop market (previously they were competing with Samsung on mobile, but had nothing to offer in contrast to Samsung's desktop products). Shortly after CES, our three companies (Intel, LG and Quanta) got together to begin working on the production path for the LG V300. It was a very rewarding experience to begin working with LG, engaging in discussions with them about their customers and business goals for the project. What I did not expect, however, were the complexities involved in driving design intent during the tooling phase. The above photos show the first run PVT (Production Validation Test) units - complete with warped parts, hand-painted lenses and parting lines which appear to have been gnawed upon by chipmunks prior to delivery.

On top of that, LG marketing had made some decisions about materials and color that presented some new challenges. They opted for a opalescent white paint (which emits a gaudy rainbow hue when looking at it from various angles) with silver accents...more consistent with the LG design language and the tastes of the Korean market. They were right about all of this, the product was a great success in Korea, but gone was the carbon color scheme which worked so well to dress the vents and IO in the back and worked to reduce the visual effect of parting lines.

I was also rather disappointed to see that rubber feet had been added to the base of the system...when the design intent called for the entire bottom of the system to be rubber. Suddenly the additional bottom panel (shown now in silver) felt unnecessary, when it was once an elegant solution for assembling the base and offering a stable footprint at the same time.

A Plan Comes Together

A Plan Comes Together

a quality result - with real impact

In the end, all of that attention to detail paid off. The LG team was masterful in working with Quanta to dial in the tolerances and part quality, which ensured that the final result was worth the premium price tag. The numbers came back later in the year that the V300, LG's inaugural desktop, was outselling Samsung in Korea and was in second place (next to Apple) in the premium AIO PC market.

Today LG still produces AIO's using sleek mobile components, and for many years certain aspects of the V300 design remained as part of their signature.